Boom, Bust, Repeat? Part 4: Spend growing revenues on reducing growing cost drivers.

While the Boom, Bust, Repeat? series has highlighted lessons learned from the last 15 years of frustrating fiscal choices, there is another reason to be cautious about using this year’s revenue windfall to spend money on new ongoing programs: In future years, much of that money is already spoken for.

Schools and the rainy day fund will sweep up most—if not all—of the nearly $4 billion in unexpected revenue coming in this spring, but more and more of the state’s resources are also being directed toward the state’s growing long-term pension and health care obligations. Whether lawmakers plan for them or not—and they should—this trend is only going to continue, limiting the state’s budgetary options and putting a further squeeze on other priorities, from infrastructure spending to higher education.

Take health and social services spending, for example—which, at $49 billion, or roughly 32 percent of the current budget, has continued to climb during the recovery for variety of reasons, from growing caseloads to federal policies that are expanding eligibility for programs like Medi-Cal.

Four million Californians have enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program in the last two years as a result of the Affordable Care Act—pushing total enrollment past 12 million this year. While California’s share of this spending is largely covered by the federal government this year, state costs are expected to climb as much as $1 billion in the next four years as the federal share declines.

Four million Californians have enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program in the last two years as a result of the Affordable Care Act—pushing total enrollment past 12 million this year. While California’s share of this spending is largely covered by the federal government this year, state costs are expected to climb as much as $1 billion in the next four years as the federal share declines.

“In four years, we’re not going to get our 100 percent payment from the federal government,” Gov. Brown said in January, noting that federal rules will require states to take on 10 percent of the cost of covering newly eligible Medi-Cal recipients starting in 2017. “In the budget, there’s not a lot of money left. It’s very tight.”

Part of the reason for this budgetary strain is the $2.4 billion the state had to set aside in last year’s budget when 800,000 individuals who were eligible for Medi-Cal—but had not yet enrolled—signed up for the program. The federal government shares only 50 percent of these costs. According to the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, an additional 550,000 and 950,000 Californians will continue to fall into this category between now and 2019.

Pensions and health care obligations

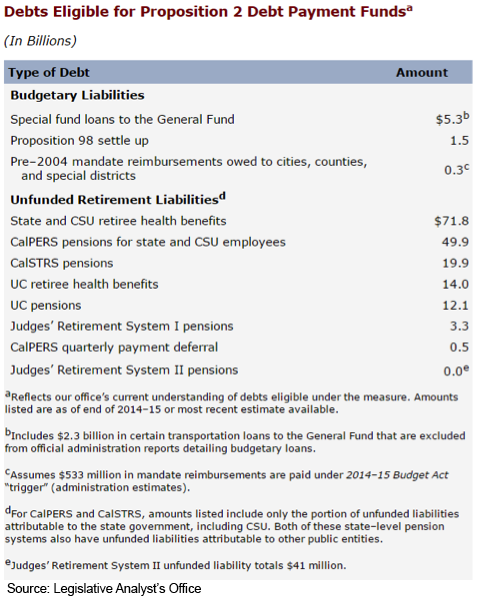

With Medi-Cal costs rising, the state has also started chipping away at its unfunded pension and health care obligations—a figure the Legislative Analyst’s Office puts at $171 billion.

To the Administration’s credit, it is taking on these issues, but budgetmakers must keep in mind these obligations will continue to take up more and more precious resources for years to come.

In 2006, the budget set aside $6.7 billion for all of the state’s retirement and health care plans—including CalSTRS, CalPERS, and pensions for judges and other state officials. The January budget sets aside just under $12 billion.

While the state’s contributions over the last decade have nearly doubled, the budget itself has grown by only 25 percent. The Administration acknowledges that it will require 30 years of spending at this rate to pay down unfunded teacher pensions alone.

“If we don’t take any action, we’re looking at hundreds of billions of dollars that we owe,” the governor said in January, highlighting the Administration’s plans to renegotiate the state’s contribution amount to some of these funds. “If we don’t rein things in, then down the road there will be drastic cuts.”

To ease this fiscal pressure, the state has another tool at its disposal: the new budget reserve created by Proposition 2, which is expected to include at least $4 billion by the end of the year. While half the funds in the reserve must be saved for a rainy day, the other half can be used to pay down long-term debts.

Because $1.6 billion in the reserve is left over from the state’s old reserve mechanism and is not subject to Prop 2’s rules, the state may be able to direct almost $3 billion this year toward unfunded pension and health care obligations—and possibly more if revenues continue to come in higher than expected.

This may be too much for a single year, but it’s an option—one that may help lawmakers make future budgets easier to manage.

——

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this blog mistakenly stated that the state is currently spending $1 billion for a subgroup of Medi-Cal recipients during the initial implementation the Affordable Care Act. Instead, net costs are expected to rise in four years for that group to an annual $1 billion payment as federal payments decline.

NEXT > Part 5: Where to spend this year’s windfall

Read the rest of “Boom, Bust, Repeat?”