(Photo Credit: Violeta Vaqueiro)

Editor’s Note: In its Financing the Future series, CA Fwd seeks to broaden this year’s critical conversation about tax reform, inviting experts from around the state to consider the long-term implications of tax proposals moving toward the 2016 ballot—and to share their views on whether they meet CA Fwd’s criteria for a sustainable tax system.

I LIKE paying taxes. With them, I buy civilization. – Oliver Wendell Holmes, US Supreme Court Justice, 1902-1930

A modern society is built on a reliable stream of public revenues that enable the investment in vital infrastructure, schools, public safety as well as environmental quality and overall quality of life. Pleasant, well-managed communities become strong attractors for talented people and business investment. Therefore, a reliably funded, well-managed public sector is essential for growing and maintaining global economic competitiveness.

California Forward’s recently published Financing the Future (Chapter 3) is a highly informative document that clearly lays out current proposals and helpful frameworks for considering tax reform.

Looking through the lens of economic opportunity and competitiveness, how does our tax structure in California encourage or discourage business and job growth for the economy of the future?

First, any tax structure is a complex system of interrelated impacts and incentive structures. Turn one dial, and impacts ripple across the system, potentially destabilizing well-functioning components and creating added complexity and economic drag. Attempting to compare states by looking at different types of taxes separately can be misleading as it misses the full picture of the relative tax burden for business across states.

Second, the economy is a highly diverse place with very different industries, and within each industry, very different types of employers. The impacts of various taxes and regulatory fees can differ widely across companies. In California, there is an additional dimension of variation between the coastal and inland economies. For example, a tool and die shop (i.e. machine shop) located in the Bay Area is likely to be working closely with technology companies on prototyping or producing highly specialized components. The business pressures it experiences are different than those faced by a similar type of machine shop located in Central California. While the rising cost of workers’ compensation may top concerns for some tool and die shops in the state, those working hand-in-hand with technology and other high-value industries rooted in the Bay Area are more likely to be concerned about finding the skilled workers they need.

Similarly, considerations for reforming the taxation of commercial property would have uneven impacts across different types of employers. Senate Constitutional Amendment 5 (Hancock and Mitchell) would require the annual assessment of commercial and industrial property at fair market value, removing commercial property from the cap on assessed value imposed by Proposition 13. Currently, commercial and residential property is assessed based on the value at point of sale, and increases are capped at 2 percent per year. With a split roll, large multi-state and multinational corporations that do business in California but have their production facilities outside the state could experience a comparative advantage over similar businesses that do produce in the state. According to the State Board of Equalization, the implementation of the split roll is estimated to generate $5 billion in new annual state revenue (roughly 4 percent of the state’s total budget) and cost $1 billion in new expense annually.

Third, as the economy continues to transform, how do we ensure that the tax structure evolves with it so we can continue to invest in the future? Technological advance and changing preferences are major drivers of structural economic change, and they progress at a faster rate than our public administrative systems. In order to reap the benefits that come with change, we need to adapt to the changing context and encourage the development of new technology and opportunities.

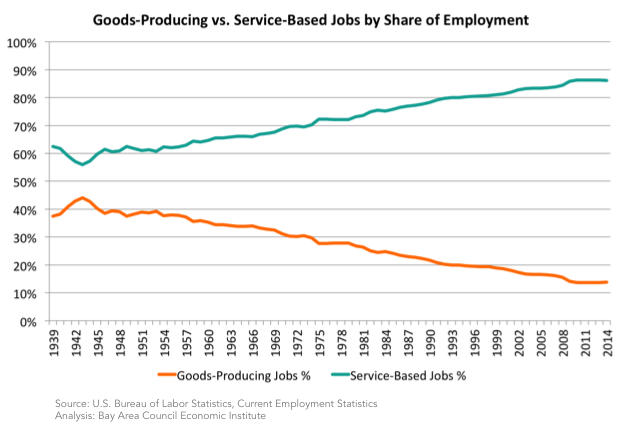

- Over the last 50 years, the US economy has moved steadily from a goods-producing economy to a services economy. Midcentury, services accounted for 60 percent of economic activity, and today it is close to 90 percent (Chart 1).

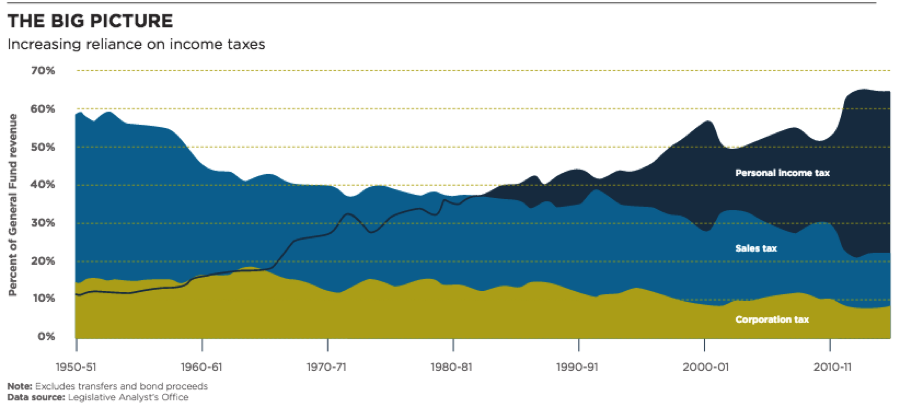

- Sales tax (on goods) represents a significant source of tax revenue for state and local governments, but it is diminishing as a share of total revenue. As a result, the reliance on income tax has grown (Chart 2), as described in Financing the Future (Chapter 3).

- Senate Bill 8 (Hertzberg) would apply a sales tax on a select set of services, lower the sales tax on goods, and lower personal income taxes in an effort to reduce volatility in state revenues. Many questions remain including whether business-to-business services or rental costs for housing would be exempted. In this time of escalating income disparity, some question whether any reduction in personal income tax for high-income earners should be considered.

- The gasoline tax is the major source of federal and state transportation funding, but as people drive less and drive more fuel-efficient (and electric) vehicles, tax revenue is not keeping pace with the maintenance needs of existing roads and other infrastructure or the building of new transportation systems (see BACEI report, In the Fast Lane, pages 44-52).

- New technology platforms are emerging that enable new business and work models which policymakers have trouble defining using frameworks from the past. Platforms that enable private individuals to provide services such as rides, rooms or the lending of goods are diverse in character with some offering new opportunities for flexible and supplemental incomes. Examples from this diverse landscape include Lyft, Uber, Instacart, Wonolo and others.

There are options for leveraging tax and regulatory reform for incentivizing virtuous cycles of economic growth and community development.

In an ideal scenario, a business would succeed based on the merits of its business model and the product or service it offers. As it grows, the business offers new jobs for local residents and opportunities for other businesses that supply inputs or support operations. Opportunity expands across the community. As a result of this business and personal income growth, local and state tax revenues also grow, enabling critical investment in education and infrastructure that build the foundation for the future. A virtual cycle is set into motion.

In reality, a business, at any stage of its development, must divert much attention and energy to issues unrelated to the core business (and source of its success). These diversions are usually costly of time and money and in practice, often seem to result in little meaningful value to the community.

Below are some examples of tax and regulatory reforms that can incentivize virtuous cycles that support economic opportunity, global competitiveness, and the generation of local and state revenues.

Reduce the Complexity, Costs and Time Demands of Meeting Regulatory Requirements:

- Reform the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA): Across all industries and business size, the one reform that would have the greatest positive impact on California’s business climate is to reform CEQA in a meaningful way. While well intentioned to protect public safety and the state’s precious natural resources when originally implemented in 1970, the approval process is complex and burdensome of time and expense. The costs and delays translate into revenue losses for a business or any organization. And where speed to market will make or break a business, CEQA can prove fatal. Furthermore, the CEQA process is prone to litigation, and projects can be brought to a halt by competitors or special interests through abuse of the CEQA process for their own material gain. Reforming CEQA will require diverse stakeholders to rise above narrow self-interests that currently warp any meaningful attempts to improve the situation.

- Streamline the patchwork of local permitting requirements and cultures across the state. The permitting process for construction (e.g. installing solar panels, replacing a restaurant kitchen, or building an apartment building) can vary from municipality to municipality. Time is money for a business, and the more of it spent on permitting processes, the less of it can be reinvested in the community in the form of new jobs and local spending. Cities such as Sunnyvale have made significant progress in partnering with businesses and others who are generating new economic value locally. This has been accomplished through both streamlining the processes as well as cultivating a culture of collaboration.

Facilitate Investment in Critical Infrastructure to Enable Growth Now and in the Future:

- Shift from gasoline tax to tax on vehicle miles traveled: The use of gasoline is diminishing (reflecting the state’s environmental goals as well as growing urbanization), but the demands on our roads and highways continue to rise. A fee on vehicle miles traveled could help stem the growing funding gap for our transportation systems. California and Oregon are currently piloting programs to study road usage charges. In Oregon, 5,000 volunteers pay 1.5 cents per mile driven and are refunded each month for the gasoline tax they pay.

- Lower the threshold for voter approval of new sales taxes: According to recent estimates by the American Society of Civil Engineers, the U.S. is currently in need of $3.6 trillion to replace aging infrastructure across the nation. Modern infrastructure keeps the economy rolling, enables growth and quality of life, and it helps ensure public safety. Especially acute in the Bay Area, investment in critical infrastructure (as well as building new housing) over the last several decades has lagged the region’s needs even under normal rates of growth. Lowering the threshold for voter approval of county sales tax measures for transportation and other infrastructure finance from two-thirds to 55 percent, with a guaranteed sunset provision in each measure passed, could help regions make the investment needs necessary for sustaining economic vitality.

Incent Business Investment:

- Expand state tax credits for research and development: California’s economic strength is in large part due to the high concentration of research-intensive companies that are driving technological advance. Nationally, the U.S. trails other advanced economies in the value of R&D tax credits, ranking 27th in the world, according the Innovation Technology Innovation Foundation. The foundation also points to research that indicates R&D tax credits spur additional R&D spending and pays for itself. In order to support the continued growth of high-value, future-oriented economic activity in the state, California could consider increasing the R&D tax credit.

- Offer investor tax credit for manufacturing: Hardware and other manufacturing industries have a more difficult time attracting investment given their high capital costs and longer developmental timelines. California could implement a tax credit for investments in the state’s manufacturing base to support the development of new manufacturers and the advancement of existing producers in the state. Other states offer income and business tax credits for angel investments in specific sectors and geographies.

- Provide tax incentives for employers to adopt apprenticeship programs: Recruitment is a top concern for growing companies across the state. This is especially the case in the Bay Area where job growth is paired with a severe housing crisis. For a wide range of technical training, corporate apprenticeship programs can be highly effective for producing talented workers with the specific skills employers need. Most small and medium-sized employers feel they don’t have the means or capacity to do this on their own. Local colleges are often not well connected with employers and therefore are not well informed about the specific skills that are in demand. Establishing consortia of employers and colleges (and other training organizations) would better inform curricula, and tax incentives for employers would encourage them to engage with such regional consortia and participate in apprenticeship programs. South Carolina has been able to stimulate apprenticeships through a $1,000 tax credit per year per apprentice for participating employers.

In order to reap the benefits that come with change, we need to adapt to the changing context and encourage the development of new technology and opportunities. Ensuring that the public sector is reliably funded even as the economy transforms structurally and goes through its inevitable cycles of boom and bust, will help ensure that California’s civilization remains on the front edge of change and new opportunity into the future. If we do not invest in the future – critical infrastructure, education, environmental quality – we are investing in the past, and the past is over.

Tracey Grose is Vice President of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute and chairs State Controller Betty Yee’s Council of Economic Advisors. The opinions expressed in this piece are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute or State Controller Betty Yee.