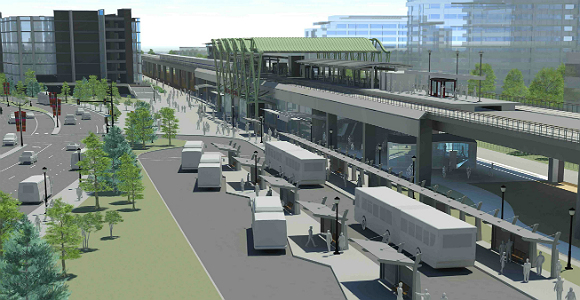

Rendering of Milpitas Station, part of VTA's BART Silicon Valley Extension Phase I (Credit: VTA)

For years, in the absence of redevelopment, it has been difficult to get infrastructure project proponents, local governments, and investors to agree on much besides this: Since the state’s popular economic development tool was dismantled in 2011, experts have been unsure how California communities were going to make tens of billions of dollars of needed investments in the state’s aging infrastructure.

In a first-of-its-kind meeting last week co-hosted by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute and the California Economic Summit, a group of more than a hundred infrastructure financing professionals discussed just how quickly that may be about to change.

Only a few months after a broad new local authority known as Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts became law, there was general consensus among experts that this new tool would provide communities with a robust alternative to redevelopment—one they can begin using right away.

“This is no longer an abstraction; it’s a tool we can use now, one whose principles are being used all around the world,” said Mark Pisano, a senior fellow at USC’s Sol Price School of Public Policy, who also serves as one of the co-leads of the Summit Infrastructure Action Team, a group that helped craft the legislation. Pisano pointed to the $25 billion Crossrail Project in London as an example of a major new infrastructure investment that is using a model akin to an EIFD, with the project managed by multiple jurisdictions and funded with a mix of public, private, and local resources.

Presenters in the meeting explored how a range of California infrastructure projects could also take advantage of this new authority—from the $4 billion extension of BART into Silicon Valley and the $1 billion restoration of the Los Angeles River to major upgrades of the Long Beach Civic Center.

Targeted funding

Unlike redevelopment, which provided communities with broad authority to invest in specified blighted areas, the new EIFDs offer local governments a broader array of financing options for a wide range of infrastructure projects, from transit stations and mixed-use developments to next-generation water systems. EIFDs can be formed by any number of cities, counties, and special districts around an infrastructure and economic development project, while also serving as a platform for multiple funding streams—including the tax increment powers once used by redevelopment agencies.

The Los Angeles City Council passed a resolution in January to become the first major metropolitan area to explore forming a district. The city is studying how EIFD funding authorities, including user fees and benefit assessments, could help finance a series of projects along a 31-mile portion of the L.A. River—transforming today’s concrete floodways into green recreational areas and new developments.

“This tool can work with a ton of different types of infrastructure,” said Jordan O’Brien, a senior manager with Arup, a design, planning, and engineering firm known for its work on projects from the Sydney Opera House to the Beijing Olympics’ Water Cube. “EIFDs can influence assets’ design for the better. It can better align them with phased development, and it can make projects greener and more efficient.”

The districts can also bridge previously insurmountable funding shortfalls.

Take the extension of BART into Silicon Valley, a project being studied by the Santa Clara Valley Transit Authority. While BART is nearing completion of a 10-mile extension of the rail system into the South Bay, the next step is to extend the system four miles further into downtown San Jose and Santa Clara.

“Funding this second phase is our biggest challenge,” said Raj Srinath, chief financial officer at the Santa Clara Valley Transit Authority. While the $4.7 billion project plans to tap several billion dollars in federal funding and local sales tax revenues, it still faces a $2.2 billion to $2.5 billion funding shortfall.

Srinath believes this gap could be partially closed by creating an EIFD around four new proposed transit stations. The City of San Jose would have to initiate the proceedings, inviting the transit agency and perhaps the County of Santa Clara to participate in the new district. Together, these local governments would jointly operate a public financing authority that would serve as a land use platform with a range of powers. The EIFD could conduct benefit assessments on property close to the new stations, for example, levying fees on businesses that would benefit from their proximity to a new transit station. It could also tap into the projected growth in property value around the stations—raising construction funds by issuing bonds supported by projected growth in local property tax revenues.

“We’re looking at all of the options, and EIFDs are definitely one of them,” said Srinath.

Improving the statute

As financing experts in last week’s meeting explored how EIFDs might support their projects, ideas for improving this new authority were also discussed—from proposals to clarify the process for forming a district (a step taken in the newly-introduced AB 313) to broader efforts to deal with disparities in how much property tax is allocated to different communities.

Questions were also raised in the meeting about how multiple agencies will be represented on the board of the public financing authority created by an EIFD.

“The statute was written to provide local governments with maximum flexibility in the way the powers operate,” said Fred Silva, senior fiscal advisor at California Forward, one of the partner organizations supporting the California Economic Summit. “Still, now is the time to clarify the statute so that implementation of the statute can proceed smoothly.”

As that process continues, it is clear the new districts will have a growing array of supporters in the infrastructure financing community.

“People have been scrambling for years in local government to figure out what to do about the huge gaps we have in infrastructure funding,” said Sean Randolph, a senior director at the Bay Area Council Economic Institute who also serves as co-lead of the Summit Infrastructure Action Team. “We know redevelopment isn’t coming back. But we’re starting to see Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts will be an important tool that will finally help us fill that gap.”

To see a copy of the Power Point presentations made at the event, please click here.